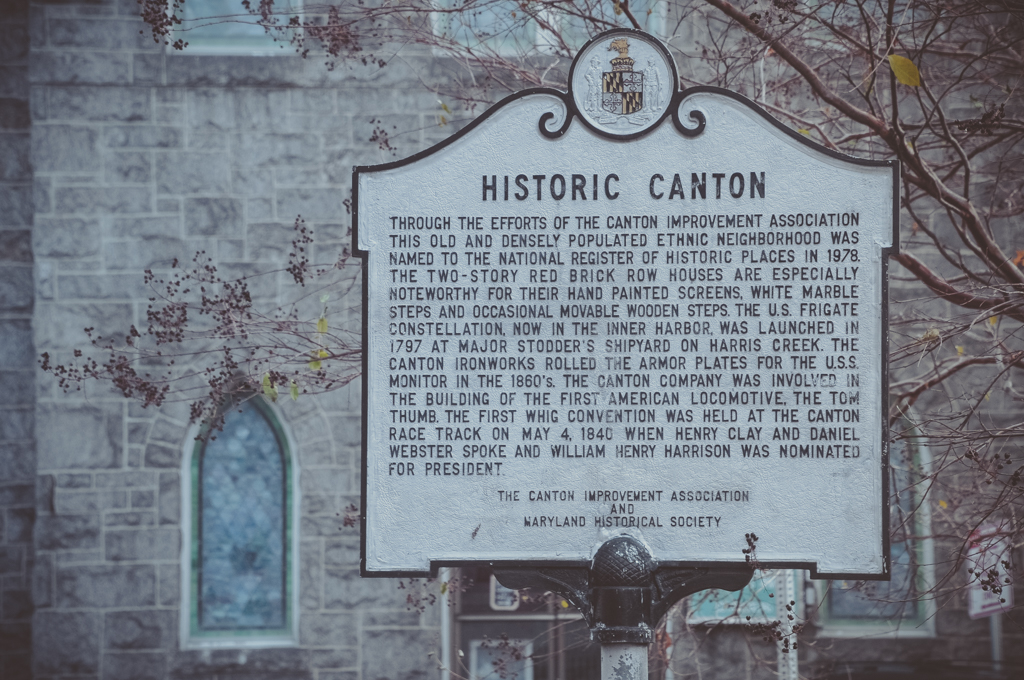

If you take the O’Donnell Street exit and follow it to the heart of the Canton area of Baltimore City, you will find yourself near the Canton waterfront at the very charming O’Donnell Square. (Expand↓)

When John O’Donnell first arrived in Baltimore in 1785, he might have considered himself very lucky indeed.

He had just stood trial in India, accused of murder at the high seas. Yet here he was, a free man.

He had hired the merchant ship “Pallas” to transport him from India with a cargo of goods from the Far East that would net him a hefty sum. The ship docked for unloading in the Baltimore harbor and John O’Donnell stepped onto American soil.

In the center of O’Donnell Square stands an imposing statue of the man for whom it is named. (Expand ↓)

Born in 1749 in Limerick, Ireland, John was just a boy when he ran away from his well-to-do family to make his own way in the world. The year 1771 found him in India, working for the British East India company as a Deputy Paymaster. Although John’s duties included managing financial transactions with local nabobs and their militarized security forces, John himself was not military. This was a civilian position much like a corporate accountant or payroll manager today.

An accountant, even for a very large and prestigious firm, might make a comfortable living, but one wouldn’t expect that person to retire young and with with enormous wealth. But after just a few short years, John had amassed a considerable fortune.

John would have been allowed to borrow money from the company toward his own enterprises, but payment was not well enforced. When change in leadership in the British East India Company brought new standards of accountability and loss prevention, it meant that John's books would have to be audited. Every time the auditors came looking for John, the deputy paymaster and his books were nowhere to be found. John wisely quit his job and absconded with his riches before the auditors could ever catch up to him.

John O'Donnell

Scroll ↓

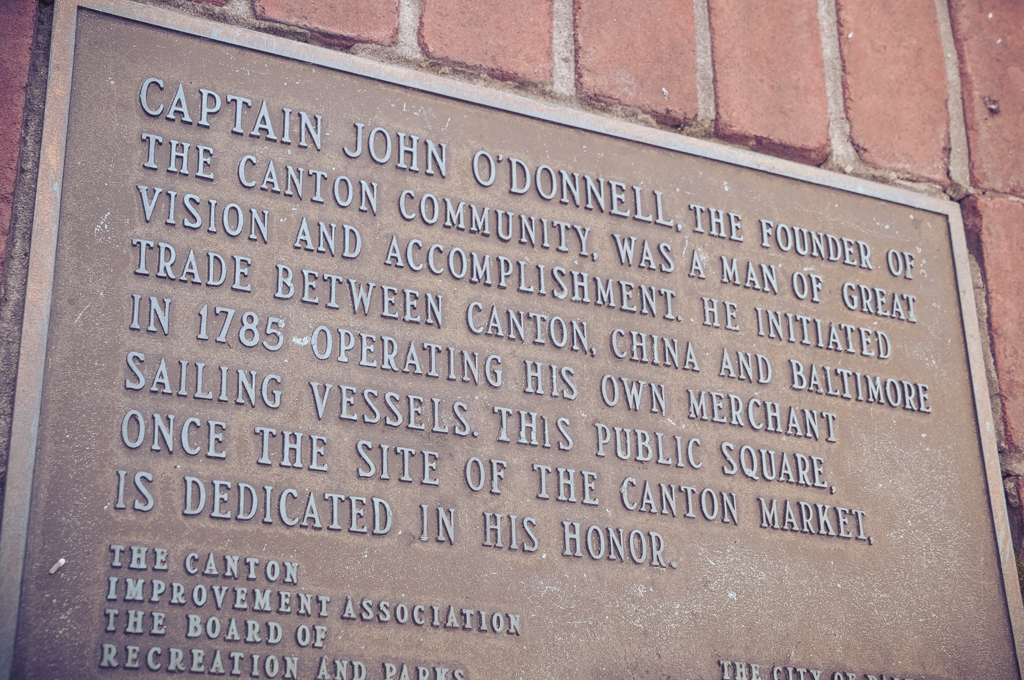

Nearby, a plaque is inscribed: “Captain John O’Donnell, the founder of the Canton community, was a man of great vision and accomplishment. (Expand ↓)

But John’s enjoyment of his wealth was to be short lived.

IN 1779, O’Donnell was transporting his considerable wealth across the desert in a caravan from Suez to Cairo. The Egyptian government, obligated under a treaty to protect British citizens on Egyptian soil, provided him a force of security guards to accompany him. As night fell on the caravan after the first day’s journey, John felt confident in his personal safety and the security of his fortune. He went to sleep in a basket atop one of the camels.

Suddenly, John awoke to a great commotion. Before he could even make sense of what was happening, the security guards had violently raided the caravan and were fleeing with everything of value.

In just moments, John went from a very rich man ready to enjoy a life of prestige and relative ease to being left with absolutely nothing. He and the few of his men who had survived the raid were forced to walk battered and naked through the blazing hot desert back to Suez with not even a canteen of water. Only John and two others of his original caravan party of ten survived the incident.

“He initiated trade between Canton, China and Baltimore in 1785, operating his own merchant sailing vessels. (Expand ↓)

O’Donnell turned to the Egyptian government for help. They had an obligation to protect him, and their security force had instead stripped him of everything he owned and endangered his life. He demanded that they give him a militia to go after the robbers and take back what was rightfully his.

But John’s pleas for redress fell on deaf ears. Once certain he would receive no reparations, John determined to quickly make another fortune.

There was an avenue that could get him there, and fast.

O’Donnell entered into partnership with James Bracey, captain of a privateer ship called the Death or Glory. Privateers, or pirates, were permitted by the English Government to roam the seas between India, China, the Philippines and Guinea looking for French ships to disable and loot, guaranteeing dominance for the British East India Company in trade with the Far East.

And so John O’Donnell set sail on the Death or Glory in search of the one thing that was always a guaranteed sale at the highest price: opium.

“This public square, once the site of Canton Market, is dedicated in his honor.” (Expand ↓)

From the 1782 trial transcript archived in The National Archives in London, we can piece together details of the incident that brought the defendant John O’Donnell to the Court of Admiralty in Madras, India.

Witnesses for the prosecution testified that the Death or Glory and another ship were anchored close together just offshore in the Java Sea when three local Malay merchant ships approached them, hoping to engage in trade.

John boarded one of the merchant ships along with a translator. The merchants opened their chests and displayed all manner of goods for sale, but John wasn’t interested. There was just one chest he wanted to look inside of, and that one was locked.

The owner of the locked chest refused to open it, which confirmed for John that there must be something valuable inside. Something extremely valuable. Like opium.

John continued to insist that the merchant open his chest. When he still would not comply, John commanded the translator to beat him and force him to open it. But the merchant fought back.

The translator fired his pistol, and a melee broke out.

Alarmed by the shot, the Malay merchants and their crewmen grabbed their weapons and prepared to attack the English ships. Men began jumping from the merchant ships and swimming towards The Death or Glory. The crew on the deck of the Death or Glory opened fire on the men in the water.

John and his translator scrambled to the pinnace that had carried them to the merchant ship and headed back. John called out to the men on deck of the Death or Glory that they need not fire on the merchants and crew in the water, as he would keep them from boarding. Witnesses said they saw John stabbing the swimmers and shoving them down beneath the waves.

Back in India, Captain Bracey filed a complaint accusing John O’Donnell of murder at the high seas.

The statue represents O’Donnell as a gaunt man with a weathered face marked by the toil and suffering that a great creator and founder must inevitably endure to leave such a legacy. (Expand ↓)

John represented himself at trial. His chief agument in his own defense seems to have been that Captain Bracey only filed the murder charge against him because Bracey was bitter about the outcome of another business matter.

John deposed his own witnesses. The transcripts suggest that while these witnesses didn’t see John commit the crimes in question, they couldn’t provide very strong affirmation of his innocence either. His defense would depend on others being able to say that they knew him to be an honorable man.

John listed about a dozen character witnesses he intended to call on his own behalf. But as the time for them to testify approached, their ship was long overdue. Days passed, and the ship never arrived.

It is not clear whether John’s would-be character witnesses were lost at sea, or if they finally arrived far later than expected. What we do know is that John pressed hard for the court proceedings to be expedited in light of the fact that some misfortune may have befallen them, and that they may never appear.

Without the missing witnesses there could not be a fair trial, and the officials had other business to get on with. All charges against John O’Donnell were dropped.

O’Donnell quickly set sail for Baltimore on The Pallas.

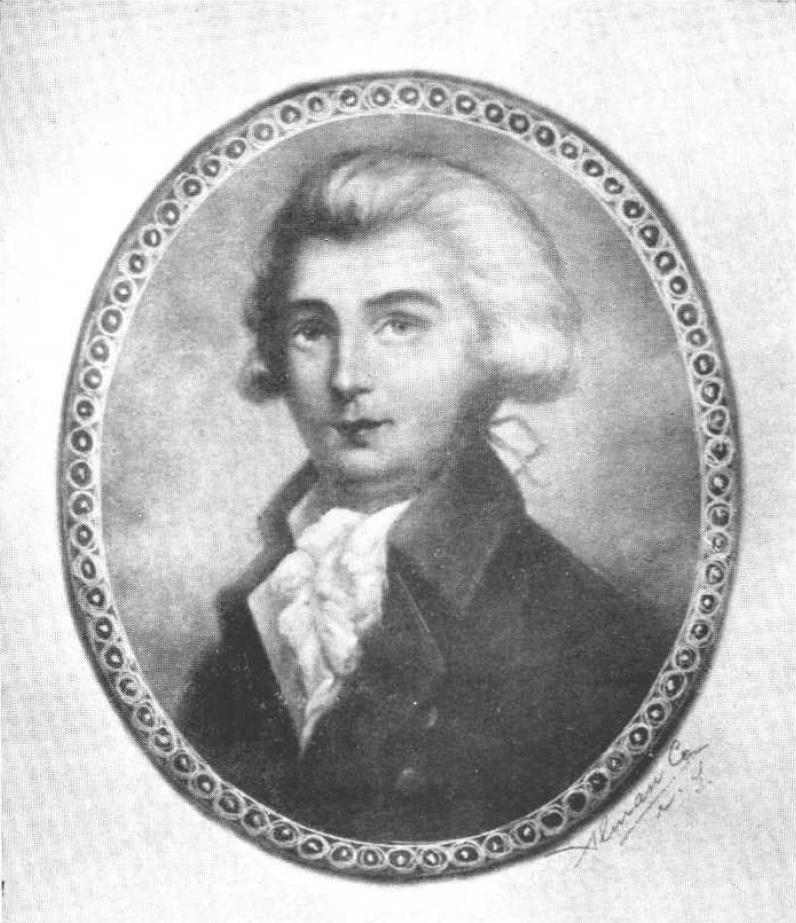

A nearby street is named for Sarah Chew Elliot, wife of John O’Donnell and the daughter of another wealthy trader in Fells Point. (Expand ↓)

When he arrived in Baltimore, John announced the sale of his cargo.

With the proceeds, he purchased nearly 2,000 acres of land on the Baltimore waterfront, which he called Canton Plantation, in honor of the Canton region of China. He had a mansion built and settled down with Sarah Chew Elliott, the daughter of a wealthy trader in Fells Point. He announced his retirement from the sailing and trade.

Sarah Chew Elliott, Wife of John O'Donnell

Sarah Chew Elliott, Wife of John O'Donnell

Painted by Charles Willson Peale in 1787

None of this would have been possible without the hefty sum that a cargo including large quantities of opium would have fetched at sale.

John had left his crew of 30-odd Chinese men, who did not speak English, stranded in a strange city without recourse. They had undertaken the journey believing there would be a return voyage to their homeland, but it was now obvious that John did not intend to sail again. There were no other ships leaving Baltimore for Asia.

Hearing rumors that there might be ships bound for Asia leaving from Philadelphia, the crew travelled to Pennsylvania. Once there, they found that they had a long wait ahead of them. They also found that it was very difficult for non-English-speaking foreigners to find work. They looked to the government for assistance. Their employer John O’Donnell had starved and mistreated them on the voyage, they said, and now he had broken his promise to ensure their return home.

Pennsylvania tried to shift the problem to Maryland, but neither Maryland nor John O’Donnell would take any responsibility. For nearly a year, the unfortunate sailors had to rely on state funds, private charity, and the sale of their few possessions in order to survive.

If you watch people enjoying the shopping and dining experiences or sitting on park benches under mature trees in the public square, it seems that relatively few take much notice of the statue. (Expand ↓)

At his mother’s insistence, O’Donnell made one more reluctant sea voyage to the family home in Ireland, and then to India to attempt to retrieve his brother. For this trip, he purchased a ship called The Chesapeake.

Under pressure from the state, he finally took at least some members of his former crew from The Pallas with him.

Once his family matters were taken care of, John would have needed to purchase ballast to weight his ship for the journey home. He offered to transport merchants and their cargo back to America as a way to offset his costs. There is no record of any other cargo that would suggest that John came out of retirement to conduct trade of his own between the Orient and America on this voyage.

Of those who do stop to gaze up at John on his pedestal, fewer read the plaque. (Expand ↓)

After arriving back home in Maryland in June of 1789, John settled into life with his wife Sarah. Josephine Lee Chatard, a relative of the O’Donnells, wrote in her brief account of John’s life that he and his wife were “leaders in the society of Baltimore Town and their unstinted and elegant entertainments unsurpassed”.

John spent the remainder of his days operating his plantations, Canton in Baltimore and Never Die in Sykesville, which were fully self sufficient. Enslaved people worked the land to provide food for his household and generated crops and other agricultural goods that they took out into the city for public sales, the early precursors of present-day farmer’s markets.

It was also customary at that time for slave-holding planters like John O’Donnell to provide enslaved labor for infrastructure projects. This was typically done with a view to enhancing the value of their own properties, but also incidentally benefited everyone in the developing areas surrounding the plantation. This was John’s contribution to the neighborhood of Canton as we know it today.

John maintained a strong sense of responsibility for his family, putting them first at all times and supporting them wherever he could. He paid for his brother's illegitimate son's 6 years' apprenticeship, and left shares of his wealth to a niece and nephew in his will.

John O’Donnell died at Canton in 1805 at the age of 56.

Fewer still will further explore the statue’s true history and significance. (Expand ↓)

This account of John O’Donnell’s life is the result of four years of research by Hans de Jong, a project he undertook after finding that his wife Victoria is the fifth great grand niece of John O’Donnell. DeJong’s research may be the first aggregation of historical documents to tell the true story of the man whose statue stands in Baltimore’s O’Donnell Square.

Much of the story is simply constructed as best it can be at the time of its writing, and is still being researched.

We do know with reasonable certainty that:

John O’Donnell probably owned only one ship during his lifetime. That ship was The Chesapeake, which he bought expressly for taking care of family matters in Ireland and India, then sold immediately upon his return.

No documentation has been found to suggest that O’Donnell was in military service let alone a captain, nor was he a sea captain. He was “Captain of Marines”, a business manager title he held aboard the Death or Glory during his partnership with privateer Captain James Bracey, and a passenger aboard other ships on which he travelled. He held an honorary title of “Colonel” as a figurehead for the local militia in Baltimore in the late 1790’s. That militia never saw battle, as the War of 1812 was still some years away. It is not known who captained The Chesapeake.

There is no evidence that John established trade between China and Baltimore. The goods that arrived on The Pallas are the last from China to enter the port at Canton during John’s time. After John’s arrival in 1785 there are no records of ships bringing goods from the Orient, let alone ships owned by O’Donnell. Even The Chesapeake delivered its paying merchant passengers and their cargo not to Baltimore, but to Perth Amboy, New Jersey.

John contributed to building the infrastructure of the Canton area of Baltimore in supplying financing and enslaved labor. However, credit for the actual industrialization of Canton belongs to his son, Columbus O’Donnell and the Canton Company.

When John died, records list livestock, furniture, and around 70 enslaved people amongst his property. Two were manumitted, and the remaining people were sold at auction

John O’Donnell’s urgent desire for riches may have made him at times an extraordinarily cruel man. He was an opportunist, an adventurer and a pirate who would exhaust all his qualities and skills, even if it meant cruelty to achieve his objectives when mastering a ship, or wit and confidence to thwart law and authority. Yet the same John O’Donnell used his great charm to gain the heart of Sarah Chew Elliott, and employed fierce resourcefulness in providing for his family. One thing is certain: John O’Donnell never wasted time nor opportunity to get what he wanted.

He just wasn’t much of a merchant.

Seasons pass and the bronze John O’Donnell stands, his outstretched arm inviting us to witness his life’s work. (Expand ↓)

Afterward by Hans de Jong (↓)

During his life John O’Donnell lost two brothers and a sister, Edmund and Charles who died in India, and Elizabeth, who died at sea during a trip from Barbados to England with her husband Dr. John Crawford. His other brother, James, appeared to have been a merchant in the West Indies, but not much is known about him. After 1785, the year John settled in Baltimore, he had only one brother left, Henry Anderson O’Donnell, who served in the Honorable British East India Company until his retirement on June 4th 1817. Despite the distance between the two brothers they had a very close relationship, with John being the eldest looking after his younger brother the best he could.

Since John settled in Baltimore and established himself almost as a local celebrity, his brother would be the one to inherit the Irish properties, however John initially tried to convince his brother to come live in America after their mother, Deborah Anderson, died in 1794. John already had appointed a power of attorney in Ireland to take care of, or better, sell the O’Donnell properties. In the end Henry Anderson O’Donnell did not make it to America because the captain of the ship who would take him to Baltimore in 1803 “mishandled” Henry’s belongings, which meant a great financial loss, and forced him to “go back to the country (= India), not for my sake, but for my children”. Here is where a very interesting, and long forgotten part of the O’Donnell family’s history comes into play.

Henry Anderson O’Donnell, while serving on the battlefields of India, maintained a relationship with a so called “Bibi”, an Indian mistress of Persian royal descend named Umbrath or Nurbrath. To this lady an illegitimate son was born in 1787, John Henry O’Donnell, commonly known as Henry. When this child was 18 months old, he was brought to Baltimore, and from there to Bucks County, Pennsylvania, by no one less than John O’Donnell on his ship the Chesapeake, arriving first in Perth Amboy and next in Baltimore in 1789. This son, Henry, was raised in Bucks county, of which period nothing is known.

Henry reappears in 1803 as an indentured apprentice at the saddle and harness business of Stephen Burrows in Philadelphia. The indenture document shows that this 6-year long apprenticeship would be financed by “an uncle who resides in the city of Baltimore”. The uncle’s name is not mentioned, but it is apparent that his name was John O’Donnell. Henry would complete his apprenticeship, own a saddle shop in Philadelphia, and eventually settle in New Germantown, Perry county, Pennsylvania, having been a saddler all his life.

Henry had seven children from two marriages, and became the progenitor of an extensive branch of the O’Donnell family. Since all ties with Henry’s father, Henry Anderson O’Donnell, and his uncle John O’Donnell were intentionally kept secret due to the illegitimacy of his birth, this branch of the O’Donnell family became a forgotten one until I discovered the will of Henry Anderson O’Donnell, who died in Limerick in 1840. In his will he leaves his “much reputed, natural son”, whom he has never seen again since 1789, 500 pounds sterling.

This inheritance led to a unique meeting around 1842 in Baltimore between the son of John O’Donnell, Columbus, and the son of his brother Henry Anderson O’Donnell, John Henry, where this inheritance was conveyed in the form of a small farm in Pennsylvania following Columbus’s suggestion and with Columbus’s assistance how to best spend the 500 pounds sterling.

Henry Anderson O’Donnell’s other son, very possibly to the same Indian mistress, Charles Routledge O’Donnell, who was raised in London and eventually inherited the remainder of the O’Donnell properties of Trough Castle, county Clare, never acknowledged the existence of his brother John Henry, which also contributed to John Henry and his descendants becoming a forgotten part of the O’Donnell family.

For further information:

Hans de Jong

vhdejong@embarqmail.com

John O'Donnell of Baltimore: A Historical Account

Storytelling and Artwork by River Irons

Historical Research and Editing by Hans de Jong

Artworks by Salomon van Ruysdael and Wenceslaus Hollar courtesy of

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Photo Gallery: Present-day Canton, Baltimore City, Maryland